|

Alternative musical notations in Chant home In the sources in which Gregorian chant has been

preserved, unintentionally a history of the conflict between letter and

spirit can be red in an exemplary way. The problem the philosopher Plato (427

– 347 B.C.) already had with script (see: Phaedrus) can be recovered in the

Gregorian chant sources continually again and continually in an other way. Essentially the following thought

underlies that problem: “when something is being fixed it gets lost

irrevocably, yet we seem eager to fix it just in order to preserve it”, or

more generally: “when the truth or the sense of life is being fixed, then

that truth or that sense gets lost definitively, yet we seem eager to fix

that truth”. When it concerns music in general, or Gregorian chant in

particular, this means: “When music is being fixed, then that music gets lost

definitively, yet we want to fix music just in order to preserve it”. Therefore a remarkable paradox lies in

this thought. For the Carolingians who fixed Gregorian chant wanted to

achieve by that fixation that Gregorian chant just not should get lost; on

the contrary, they thereby wanted to achieve that it should continue to exist

all over their empire in the same way, by which the unity in that empire

should be promoted. In a certain sense they did achieve

that, for Gregorian chant has been preserved up to the present. But Gregorian

chant having been fixed that Gregorian chant has not remained unchanged. On

the contrary, every new way to fix the repertory resulted in a change of that

repertory itself continually again. Therefore Gregorian chant as we still

know it at present (roughly having been formed during the so-called “Rijke

Roomse leven” (Rich Roman life) from let us say 1908 until 1974) has, except

in a formal sense, not to do so much with Gregorian chant which the

Carolingians wanted to fix. Also the unity of the Carolingian Empire has not

outlived the Carolingians indeed. In the history of Gregorian chant in

outline seven periods can be pointed out from the perspective of letter and

spirit, periods which cannot strictly be separated and each of which bears

something of the other in itself: 1. The period of the oral tradition;

roughly the period from Constantine the Great till Charlemagne. In this

period Gregorian chant “came into being”. But that “coming into being” was by

itself already a transformation of Jewish, Greek and Roman traditions from as

many liturgical, folkloristic and classical contexts.

View at the oral tradition; gregorian,

ambrosian and old roman chant in 20th-century

transcriptions of 11th-century manuscripts. 2. The period of the fixation of the

song-texts only; roughly from 600 till 1000. In this period the “original”

freedom and variation in choosing the song-texts were changed more and more

into a code of law with precise song-texts for specific liturgical moments.

Mont Blandin, early

9th century (Brussels, Royal Library 10127-10144) 3. The period of the fixation in

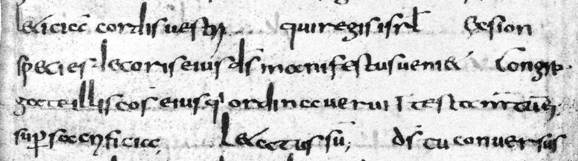

adiastematic neumes; roughly from 800 till 1200. In this period the

“original” freedom and variation in the melodies were fixed further and

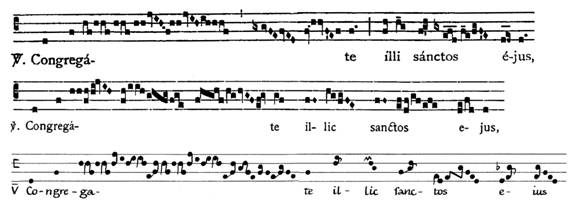

further in pricesely dictated melodies.

Laon, early 10th

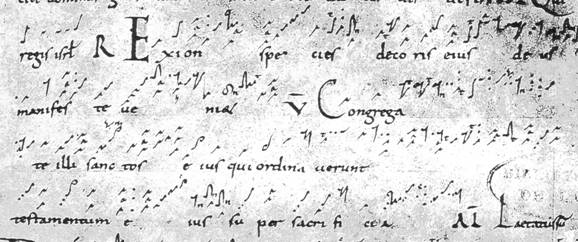

century (Laon, Municipal Library Codex 249) 4. The period of the fixation in

diastematic neumes; roughly from 1000 till 1400. In this period the

“original” freedom and variation in the ornaments and style of the repertory

were uniformed further and further to one style without ornaments.

Dijon, early 11th

century (Montpellier, Library of the medical faculty, Codex H 159) 5. The period of the revision of the

repertory; roughly from 1100 till 1600. In this period the repertory

meanwhile appeared to be alienated so far from its “original” vitality that

it was adapted more and more to new liturgical and musical fashions. Köln, Minoritenkonvent, 1299 (Köln,

Dombibliothek, Codex 1001b) 6. The period of the “new” Gregorian

chant; roughly from 1400 till 1900. In this period European national and

local self-confidence are awaking and Gregorian chant is going hand in hand

with the new liturgical, folkloristic and classical traditions, to succumb to

it finally in spite of (or just thanks to?) the invention of the art of

printing.

(Neo)-Medicea Gradual

(between 1615 and 1901) 7. The period of the reconstruction of

the repertory; roughly from 1800 till now. In this period the “original”

Gregorian chant is again being sought after. But this seeking particularly

concentrates on already codified manuscripts from the fourth period. Besides

this quest is made from neo-romantically and modern shaped western ears,

having as main object to set up a new code of law for the repertory.

Graduale Lagal (The

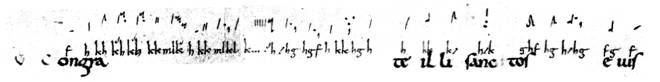

Hague, 1984) Consequently, when musical notation is

concerned, there is continually a question of adapted musical notations for

an object or a target group for which the existing traditions have lost their

sense. When the “original” Gregorian chant is

concerned, one could defend from a certain point of view that only the

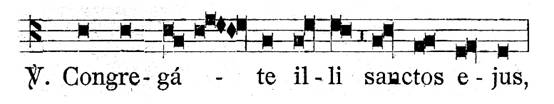

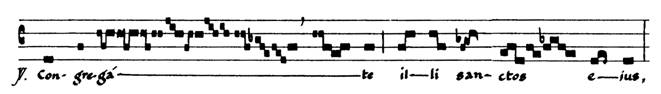

musical notations from the periods 3, 4 and 7 are relevant for a

reconstruction. From these three periods a number of examples has been

presented below

by means of the end of the offertory “Deus enim firmavit”. When the spirit of the “original”

Gregorian chant is concerned, we are especially committed to the first three

periods. However, except in sources which are illegible for us from a musical

point of view, these periods are hardly accessible any longer in the West. In

the East, on the other hand, are still traditions in existence functioning

under circumstances which are allied to those of Gregorian chant from before

the Carolingians. In order to trace the spirit of Gregorian chant one has to

listen therefore to the traditions from particularly the Balkans, Turkey,

Egypt, Tunisia, Iraq, Iran and India. Geert Maessen Amsterdam, September 2003 (translation Reinier van der Lof) |