|

Gregorian chant as

sung poetry home Gregorian chant is, just like reading

from Torah or Koran and just like recitation from Iliad and Odyssey,

essentially sung poetry. That is to say, poetry which is housed in all those

texts and stories which associate individual man with that which surpasses

him, which is beyond time and space, which is inexpressible; call it the

unnamable, the eternal, the absolute, Atman, Brahman, Allah, God or if you

like Nothingness. The most important differences lie in

the language and the book. No Hebrew, Greek or Arabic, but Latin, the

language of the Roman Empire. No Torah, Greek classics or Koran, but –

especially – the Psalms, those beautiful Jewish texts from the first

millennium before our western era. Only one subject is in there: the link

between man and God.

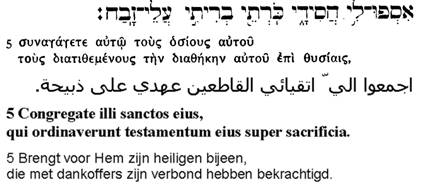

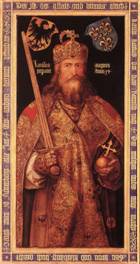

Psalm 50(49), vers 5 The Gregorian repertory was recorded

for the first time under Pepin the Short and Charlemagne, as a means of power

to achieve unity in the carolingian empire. In order to impart more prestige

to the repertory it was ascribed to pope Gregory the Great (c 540 – 604), who

possibly figured in arranging the songtexts, but presumably had nothing to do

with the actual music. Since the Carolingians the repertory has been copied

continually, so that hundreds of manuscripts from the 9th up to and including

the 12th century have yet been preserved, comprising some 10.000 songs.

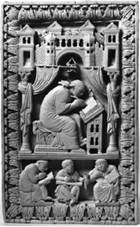

Gregory the Great (Trier, Vienna and Saint Gall, 9th

and 10th century) By those manuscripts the music had been

fixed for the greater part, but musical notation was not unequivocal and

therefore continuously in development until, in the 19th century, nothing was

left to chance any more. Musical notation has had a hardly to be overestimated

influence on the further course of western music history. It also has made

possible new musical developments like polyphony and harmony, which grew

dominant in the renaissance to such a degree that even Gregorian chant was

drastically revised.

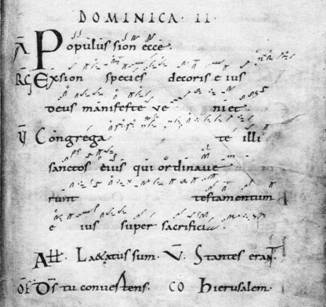

Cantatorium of Saint Gall (early 10th century) The vital origin of Gregorian chant

precedes many schisms. That between Roman Catholics and Protestants in the

16th century, to begin with. Next that between western and eastern

Christians, which seems to be definite since the 11th century. Moreover – not

unimportant – that between Christians and Muslims. This last one is less

strange considering that Islam was regarded as an Arian form of Christianity

at its rise in the 7th century.

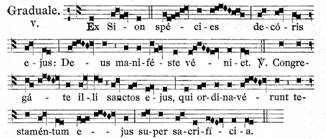

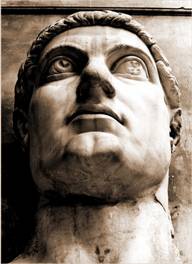

(Neo)-Medicea (between 1615 and 1901) The most important schism however is

perhaps that between musical notation and oral tradition (i.e.: letter and

spirit). Gregorian chant has come into being between Constantine the Great

(273 – 337) and Charlemagne (742 – 814). That means that it had an oral

tradition of at least four centuries. It is important to state that the

musical traditions of the Orient essentially have remained oral traditions up

to nowadays. Add to this that Constantine removed the centre of culture to

Constantinople as early as 330. In spite of the graves of Peter and Paul in

Rome it remained so until it passed into Turkish hands and finally (only as a

result of the Ataturk nationalism in the 20th century) was called Istanbul.

Tuesday the 29th of May 1453 is the turning point in that flowing transition

of the cultural centre of the West into that of the East.

Constantine Charles It is not strange therefore that what

one can read in the oldest western manuscripts makes very greatly think of

that which one can hear even this very day with the best Islamitic singers.

In a comparable way one can also find again much of Christianity of the dark

middle ages in the lay-out of the mosque and the posture during praying.

Church Mosk It would be great if Gregorian chant

could contribute to the rapprochement of the various world religions as also

to that of religious and non-religious. However, that is only possible if it

is considered as that what it is: sung poetry. Geert Maessen Amsterdam,

August 2002 (translation

Reinier van der Lof) |